CONTENTS

- Ligament Tears

- Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL)

- Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL)

- Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL)

- Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL)

- Meniscal Tears

- Patellofemoral Pain/Dysfunction

- Patellar Tendonosis vs. Patellar Tendonitis

- Cartilage Defects

- Osteoarthritis

- Quadriceps Strain

- Hamstring Strain

- Calf Strain

- Hamstring and calf treatment plans

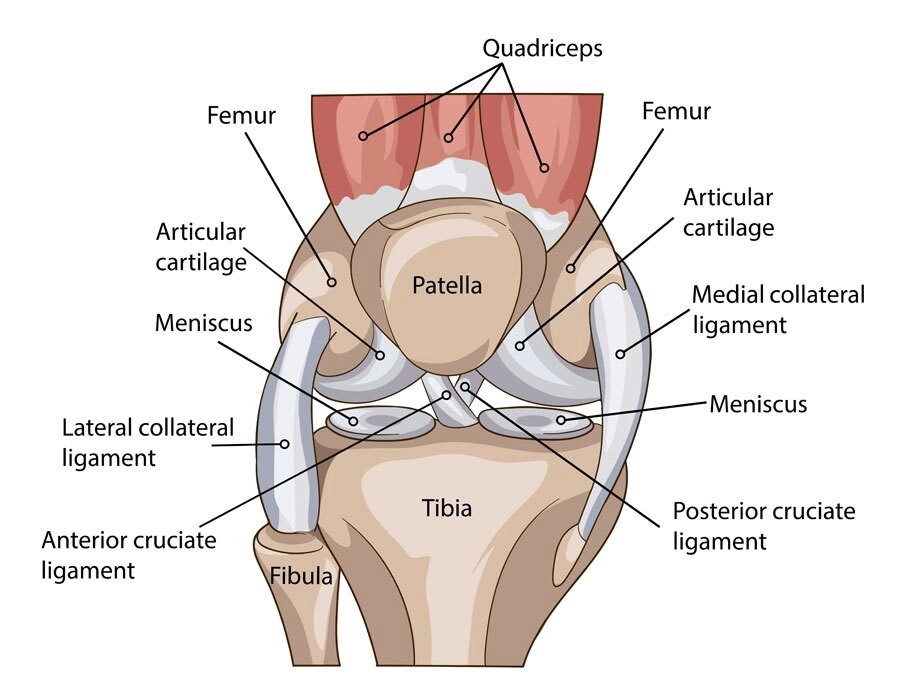

Knee anatomy explained

The knee is a hinge joint. It is the femur’s meeting point (thigh bone) with the tibia (shin bone). With minimal bony approximation, the knee joint is heavily reliant on soft tissue structures for stability. These include ligaments, the meniscus, and tendons. Soft tissues include ligaments, meniscus, and tendons.

An additional joint in the knee is the articulation of the patella (kneecap) with the femur. Numerous injuries can occur, some acute and some chronic, and many surgical procedures are used to address knee injuries and pain.

Most common knee injuries

Read on to learn about the most common knee injuries including symptoms, causes, risk factors, and treatment options.

Ligament Tears

There are four ligaments in the knee – two cruciate ligaments (ACL, PCL) and two collateral ligaments (MCL, LCL). Ligaments connect bone to bone, and these four ligaments serve to provide stability to the knee joint.

The knee ligaments can be injured in a multitude of ways. Since they check the knee’s movement in specific directions, injury usually occurs when the knee is twisted or torqued abnormally.

Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL)

Probably the most ‘famous’ of the four knee ligaments, the ACL is most commonly injured by high torque within the knee causing a shift, tearing the ACL. Injury may be associated with an audible “pop” and immediate joint effusion (swelling within the joint). Injuries can be related to a direct blow to the knee.

However, ACL injuries often occur with no contact at all. They can be isolated or associated with related injuries to other structures, including the meniscus, articular cartilage, or the other knee ligaments (MCL).

- ACL reconstruction: An arthroscopic surgical procedure performed to restore the normal function of the ACL using a tissue graft. The surgeon will remove the original ACL tissue, drill new tunnels into the femur and tibia, and use a tissue graft to reconstruct the ACL. Surgeon preferences on graft type and surgical technique vary.

Post-op rehabilitation is essential in protecting the repair, restoring normal range of motion (ROM), reducing post-op swelling, and recovering normal muscle function. As restoration progresses, your physical therapist will begin to include additional exercises to maximize strength, endurance, power, and coordination to prepare for a return to normal activities.

Typically, rehabilitation following an ACL reconstruction can take up to and beyond 4-6 months, depending on associated injuries and goals following surgery. Your surgeon and therapist will work together to determine your readiness to return to sport.

Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL)

Less commonly injured than the ACL, the PCL also provides stability to the knee. The PCL checks the excessive motion of the tibia posterior on the femur and rotatory torque in the knee.

Isolated PCL injuries aren’t common but do occur, often due to a direct blow to the tibia while the knee is bent. The PCL is more commonly injured in combination with other ligaments and structures in the knee due to a high velocity, high torque injury. Suspected PCL injuries should also include evaluation of neurovascular structures.

- PCL Reconstruction: Like an ACL reconstruction, the PCL is also repaired using a tissue graft to restore normal position and function. Repair is complicated due to the knee and vessels’ anatomy and nerves close to the PCL. Post-operative rehabilitation is similar to post-op ACL reconstruction with some differences. Most importantly, protecting the repair while restoring ROM, increasing strength, and reducing swelling are your physical therapist’s primary goals. As rehabilitation progresses, your therapist will work with you on restoring function and preparing you for a full return to activity.

Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL)

Another commonly injured ligament, complete tears of the MCL, are uncommon. Typically graded in degrees, an MCL sprain can be extremely painful (more so than ACL/PCL injuries).

Often the MCL is injured because of a direct blow to the outside of the knee, causing excessive medial gapping. It can also be damaged due to high velocity, high torque activities such as pivoting or twisting.

- MCL Reconstruction: Surgical reconstruction of the MCL is uncommon. Depending on other injured structures in the knee, an MCL sprain/tear will usually be treated conservatively with physical therapy. Because of the MCL’s anatomy and its proximity to the knee joint capsule, treatment is geared towards scarring down and allowing it to heal gradually. Your physical therapy will be focused on reducing pain, the gradual restoration of ROM, strengthening, and progressing to return to activity/sports.

Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL)

The LCL is also not commonly injured. Its primary function is to prevent “gapping” of the knee joint’s lateral (outside) knee joint. Typically, the LCL is injured in combination with other knee structures (PCL, ACL, posterior joint capsule) due to high velocity, high torque injuries resulting in dislocation of the tibia on the femur.

- LCL Reconstruction: Surgical repair involves using graft tissue to reconstruct the LCL. Other structures damaged will also be repaired depending on the injury and surgeon preference. Rehabilitation will focus on protecting the repair, restoration of ROM/Strength, and gradual return to normal activities. Other concomitant injuries to adjacent structures typically complicate physical therapy. Physical therapist/surgeon communication is essential.

Meniscal Tears

The medial and lateral meniscus are circular, cartilaginous, wedged-shaped structures that sit on the tibia and serve to 1) provide shock absorption and 2) deepen the socket for the femoral condyles.

The medial meniscus is more commonly torn than the lateral meniscus due to its relative immobility. Tears in the meniscus can occur in multiple areas (or zones) and can be of various shapes and sizes (radial, bucket-handle, etc.).

- Meniscectomy: An arthroscopic surgical procedure where the damaged area of the meniscus is trimmed and removed. Advances in arthroscopic technology have made this procedure relatively simple as compared to the past. Physical therapy following a meniscectomy is focused on restoring ROM, strength, balance, and returning to normal activities. Typically, treatment can start immediately following surgery, and full recovery can be attained within 6-8 weeks, depending on the procedure’s scope.

- Meniscus Repair: An arthroscopic surgical procedure in which the torn meniscus is repaired. Multiple factors determine whether or not the meniscus will be repaired, including age, type of tear, location of the tear, and tear size. The surgeon will use a suture to repair the torn meniscus, being careful to retain its original structure/shape. Physical therapy following a meniscal repair is more complicated than following a meniscectomy because of the healing time required for the repair. In rehab, your therapist will follow ROM and activity guidelines and work with your physician to ensure that the repair isn’t stressed. The meniscus will take up to 6-8 weeks to heal, at which point rehab can progress more quickly.

- Meniscus Replacement: The least common procedure for meniscal injuries, a replacement is usually reserved for young, active patients with severe meniscal injury. A meniscal graft will be surgically introduced into the joint and sutured into place. Post-operative rehabilitation will be slower and will follow specific pathways to allow for healing. Good surgeon/physical therapist communication and teamwork are critical.

Patellofemoral Pain/Dysfunction

The patella (knee cap) is a sesamoid bone that articulates with the distal femur and serves to increase the quadriceps’ leverage during knee extension. It also helps to provide some protection to the anterior knee joint. Because of the patellofemoral joint’s dynamic nature, there are many causes of dysfunction resulting in anterior knee pain.

While some causes are related to anatomical variances, many patellofemoral pain causes are dynamic and can be addressed through a comprehensive, individual physical therapy treatment plan. Your physical therapist should assess the entire kinetic chain (from foot to hip/core) when evaluating you. They should consider many factors, including walking/running biomechanics, standing posture, muscle length and strength throughout the lower extremity, and hip/core strength.

Typically patellofemoral pain/dysfunction is treated non-operatively. However, in certain instances, surgery may occur. Procedures may include:

- Arthroscopic Debridement – a debridement of the underside of the patella

- MPFL Reconstruction – a reconstruction of the medial patellofemoral ligament

- Lateral Release – the surgical release of the lateral retinaculum

- Fulkerson Procedure – a surgical shift of the tibial tubercle

- HTO (High Tibial Osteotomy) – a surgical realignment of the lower extremity

Patellar Tendonosis vs. Patellar Tendonitis

Tendons connect muscle to bone. Therefore tendons serve to transfer energy from a contracting muscle to move the body part. The quadriceps (thigh) muscle is a large, powerful muscle on the front of the leg. When it contracts, energy is transferred through the quadriceps tendon, patella, and patellar tendon to extend the knee. If there is excessive force, overuse, and/or a muscle imbalance, micro-trauma in the tendon can occur.

Tendonitis refers to active inflammation in the tendon tissue. Tendonosis refers to degenerative changes in the tendon. Both conditions are related, although tendinosis is more common due to ongoing micro-trauma, with or without inflammation. Over time, this condition results in pain and loss of function.

Physical therapy treatment will focus on unloading the affected tendon through activity modification, exercises focused on strengthening the entire kinetic chain, and improving technique and biomechanics during activity.

Additionally, instrument-assisted soft tissue mobilization can be used to kick-start the healing process in the degenerative tissue. This technique can assist in tissue remodeling in combination with ongoing activity prescribed by your therapist.

Cartilage Defects

At its articulation with the tibia, the femur’s distal end is covered by protective hyaline cartilage. Injuries and lesions to the hyaline cartilage are common in traumatic knee injuries.

An osteochondral defect (OCD) can occur, leaving a “hole” or “crater” in the hyaline cartilage, which may or may not leave that section of bone exposed. There are several categorizations and grades of cartilage lesions within the knee, so the prognosis depends on multiple medical factors.

Surgical treatment is usually the only option, although physical therapy can assist with activity modification, patient education, and strengthening.

- Surgical Intervention: From arthroscopic fixation (“nailing”) of the lesion to more advanced techniques such as OATS, ACI, Carticel, or an osteochondral bone graft, there are multiple medical options to discuss with your surgeon. Physical therapy following any of these procedures is complicated by protecting the repair and healing time. Many patients will be restricted in weight-bearing and ROM for some time. Your physical therapist will work with your surgeon to develop the best pathway for your recovery.

Osteoarthritis

Chronic trauma and breakdown of the hyaline cartilage in the knee is also referred to as Osteoarthritis (OA) or “wear and tear” arthritis. Osteoarthritis occurs when the cushioning and protective hyaline cartilage breaks down, resulting in decreased joint space and degenerative changes in the cartilage. This can become quite painful, especially during weight-bearing activities.

Conservative treatment for OA includes physical therapy. Your physical therapist will educate you on weight-management and activity modification, as well as prescribing exercises to strengthen and stretch the muscles surrounding the affected joint. Remaining active is an integral part of OA treatment, and your physical therapist can help you find activities that reduce the load on your joints.

- Total Joint Replacement: Usually the last resort option for patients with severe OA and pain resulting in loss of function, a total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a major surgical procedure that generally results in a brief hospital stay. The surgeon will remove the femur and tibia end, replacing them with prostheses that will serve as your new knee joint. Physical therapy following TKA is geared towards promoting safe mobility initially. As you gain confidence and the ability to bear weight, your physical therapist will work on regaining ROM, strength, and, most importantly, function.

Common Lower Body Injuries

Several injuries can occur in the lower extremity that may or may not be associated with a particular joint. These typically present as muscle strains (or pulls) that can limit one’s abilities and become nagging and chronic.

Quadriceps Strain

The term ‘quadriceps’ refers to a powerful set of muscles on the front of the thigh that serves primarily to extend (or straighten) the knee joint. 4 primary muscles make up the quadriceps complex – the rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius, and vastus medialis.

These four muscles originate on the femur (except for the rectus femoris) and come together to form the patellar tendon. The rectus femoris originates on the pelvis and serves as a hip flexor and an extensor of the knee.

Muscle strains usually occur when a muscle is stretched beyond its limit, tearing the muscle fibers. They frequently occur near the point where the muscle joins the tendon’s tough, fibrous connective tissue. A similar injury occurs if there is a direct blow to the muscle. Muscle strains in the thigh can be quite painful.

Once a muscle strain occurs, the muscle is vulnerable to reinjury, so it is essential to let the muscle heal properly and follow your doctor and physical therapist’s preventive guidelines.

Physical therapy treatment will initially focus on rest, ice, and compression (RICE). As recovery progresses, treatments will expand to include strengthening and flexibility exercises, instrument-assisted soft tissue mobilization, and a functional progression back to sports and activity.

Physical therapy will also focus on contributing factors that may have made the individual more susceptible to injury, including patient education on dynamic warm-ups, appropriate stretching, and deconditioning/fatigue.

Hamstring Strain

Hamstring muscle injuries (“pulled hamstrings”) frequently occur in athletes. They are especially common in athletes who participate in sports that require sprinting, such as football, soccer, baseball, and basketball.

The term hamstring refers to the muscles in the back of the thigh. Three muscles make up the hamstring muscle complex – the semitendinosus, semimembranosus, and biceps femoris. All three muscles originate on the pelvis at the ischial tuberosity and insert below the knee on the medial and lateral tibia. The hamstrings serve to flex (bend) the knee and extend (straighten) the hip.

A hamstring injury can be a slight pull, a partial tear, or a complete tear. Injuries are graded on a 1-3 scale. Most hamstring injuries occur in the thick, central part of the muscle or where the muscle fibers join tendon fibers. An avulsion injury, where the muscle is torn entirely from the bone, can occur at the ischial tuberosity. This injury requires surgery.

A hamstring strain results from muscle overload that occurs when the muscle is contracting as it lengthens. This happens in sprinting activities when the muscle is contracting during push-off.

Risk factors for suffering a hamstring strain include deconditioning, inflexibility, muscle imbalance, muscle fatigue, and activity level.

Physical therapy treatment will initially focus on rest, ice and, compression (RICE). As recovery progresses, treatments will expand to include strengthening and flexibility exercises, instrument-assisted soft tissue mobilization, and a functional progression back to sports and activity.

Physical therapy will also focus on contributing factors that may have made the individual more susceptible to injury, including muscle imbalances, patient education on dynamic warm-ups, appropriate stretching, and deconditioning/fatigue.

Early treatment with a plan that includes the RICE protocol and physical therapy has been shown to result in better function and quicker return to sports.

Calf Strain

The calf consists of 9 different muscles. The gastrocnemius and soleus are the largest and most active muscles in the region. They work along with the plantaris muscles, which attach to the heel bone. The other six muscles in the calf help promote knee, toe, and foot movements.

A calf strain is an injury to the back of the leg muscles and is caused by overstretching or tearing any of the calf’s nine muscles. It can happen suddenly or develop slowly over time. Walking, climbing stairs, or running can be painful, difficult, or impossible with a calf strain.

Typically, individuals who sustain a calf strain notice a sudden, sharp pain in the back of the leg. The most common muscle injured when a calf strain occurs is the medial gastrocnemius. This muscle is on the inner side of the back of the leg. The injury usually occurs just above the midpoint of the leg (between the knee and ankle). This area of the calf becomes tender and swollen when a muscle strain occurs.

The severity of the injury usually guides the treatment of a calf strain. Physical therapists can help guide treatment that may speed your recovery.

Specific modalities, such as ultrasound or therapeutic massage, may be helpful in addition to exercise-based therapy. It would be best to work with your physical therapist to determine the treatment appropriate for your condition.

Common treatment options for hamstring and calf injuries

Ultrasound, electrical stimulation, and/or other methods to help control your pain. Physical therapists are experts in prescribing pain-management techniques that reduce or eliminate the need for medicines, including addictive opioids.

Range-of-motion exercises. Your strain may be causing increased tension in your hamstring or calf. Your physical therapist may teach you range-of-motion (movement) techniques to restore normal motion in your muscles.

Manual therapy. Your physical therapist may provide “hands-on” treatments to move your muscles and joints gently. These techniques help improve motion and strength. They often address areas that are difficult to treat on your own.

Muscle strengthening. Muscle weaknesses or imbalances can contribute to calf muscle strain. They can also be a result of your injury. Based on your condition, your physical therapist will design a safe muscle strengthening program just for you. It will likely include your core (midsection) and lower body muscles. Your physical therapist will choose activities that are right for you based on your age and physical condition.

Functional training. Once your pain, strength, and motion improve, you will need to transition back into more demanding activities safely. To reduce tension on your hamstring or calf muscle, you will need to learn safe, controlled movements.

Following your physical therapist’s guidelines will also reduce your risk of repeated injury. Your physical therapist will create a series of activities based on your unique condition to teach you how to move correctly and safely.

Suffering from chronic knee pain?

An Alves & Martinez physical therapist will complete a comprehensive evaluation to determine the musculoskeletal causes of your knee or lower-body injury. Schedule an in-clinic consultation today.